“Character ultimately rules the day. People will see the truth of who you are even when you make mistakes.”

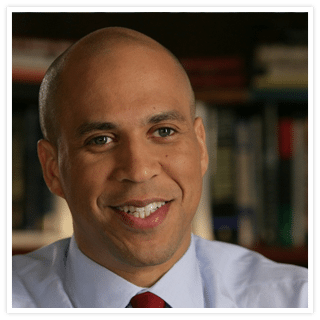

Cory Booker has served as the mayor of Newark, New Jersey—the largest city in the state—and now serves as a US Senator. Under Mayor Booker’s leadership, Newark was a leader in the nation among large cities for violent crime reduction and urban development. His political career began in 1998, after he served as staff attorney for the Urban Justice Center in Newark and then as Newark’s Central Ward councilman from 1998 to 2002. He has been recognized in numerous publications, including O magazine, Time, Esquire, New Jersey Monthly (which named him as one of New Jersey’s Top 40 Under 40), Black Enterprise (which placed him on the Hot List, America’s Most Powerful Players Under 40), and the New York Times Magazine. He is a member of numerous boards and advisory committees including Democrats for Education Reform, Columbia University Teachers’ College Board of Trustees, and the Black Alliance for Educational Options. Mayor Booker received his B.A. and M.A. from Stanford University, and a B.A. in modern history at Oxford University as a Rhodes scholar. He completed his law degree at Yale University. (www.CoryBooker.com)

the interview

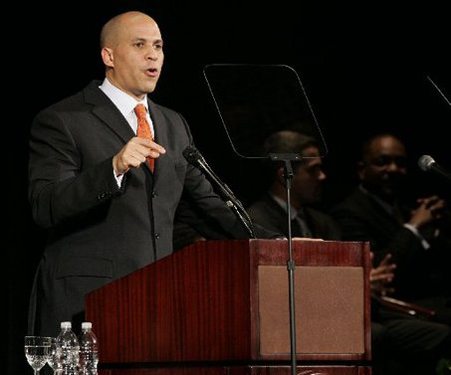

When I interviewed Cory Booker, he was the Mayor of Newark. He’s now a U.S. senator and is running in the 2020 Presidential Election. I first met Cory after I saw him speak in New York City, and I was blown away. I don’t think I’ve ever seen a more impressive orator. Needless to say, his schedule is extremely tight. Thankfully, he generously consented to a half-hour interview while I was in town. Our interview was conducted in a Starbucks at a Barnes and Noble on the Upper West Side. While riding from the Upper East Side to the Upper West Side in his car with his group of handlers, I learned that we had something in common: he also had some experience in film. His 2002 turbulent race for mayor of Newark against a four-term incumbent twice his age is chronicled in the Academy Award–nominated PBS documentary Street Fight (www.marshallcurryproductions.com) and of course, you can go learn more about Cory at his website: corybooker.com. I loved speaking with Cory and he always followed up on anything he promised. He definitely is a success story–and it’s been so fun to watch his rise. I look forward to seeing how he grows and what he continues to do as a public servant.

the epiphany

I was twelve years old and running for seventh-grade class president. I was running against three other guys, the really cool guys, and I always thought of myself as very awkward. After we’d been campaigning for a few weeks, we had to each make a speech. Then the next day the kids would vote.

The day before I had to give my speech I stayed up really late working on it and rehearsing it. It was going to be the biggest moment of my life, in front of all my peers, the entire grade. I got up to give my speech, was standing at the podium, and . . . I froze. I could not get a word out. I remember shaking violently. The paper was rustling, my hands were shaking so hard. I just couldn’t say a thing. I remember that my vice president candidate was standing next to me, bumping me, like, “What’s wrong? What’s wrong with you?” I just couldn’t get anything out. I sort of mumbled through the speech, horrified. The more that it went on, the more horrified I was. It was the singularly most humiliating experience of my long twelve years.

I remember that when it was over, I was devastated. It was one of those things where you could see the pained look on the faces of the other kids. Some kids laughed. I could see that some kids felt awkward too. The teachers seemed to be feeling my awkwardness too. Everybody did. I went home. It was the worst thing that could’ve happened. I was so embarrassed. It was just horrible.

But two things happened out of that which were great life lessons. First, after that I was just so angry and so upset that I made this oath that I was one day going to be a really good public speaker. That day I swore that I was going to get over this fear. It was kind of weird for a twelve-year-old, but I remember saying this, and interestingly, I changed my behavior after that. Any chance that I had to speak in front of people, whether it was the basket- ball team or whatever, I would stand up and try to confront this fear. I practiced public speaking and practiced public speaking and practiced public speaking. Now I’ve given speeches all around the country, to all kinds of groups and in all kinds of situations.

The second thing that helped fuel my confidence to take on this fear of public speaking was that I actually won the election! Winning the election reaffirmed in me that it isn’t the flash, it isn’t the rhetoric. It’s who you are. I think that my classmates knew me—a lot of us had been in school together since kindergarten—and they voted for the person that obviously wasn’t the most popular. The other guys really were the popular guys. Even though the only chance that I had to present my ideas and my platform was incredibly ineffective—and basically a complete disaster—people still voted for me. It made me have a lot more faith in people and the electorate and more courage just to be my authentic self. Even on your worst days, one moment doesn’t mark the entire man, so to speak.

This epiphany, that people will ultimately see the truth of who you are even when you mess up, has been tested time and time again, and has served me as long as I’ve been in public office. When I’ve messed up publicly in a major way, or embarrassed myself and done something stupid, the lesson is always reaffirmed: people are forgiving and loving and they make allowances for inadequacies, as long as you’re honest and own up to mistakes—and they know your character to be true. As bad as the day might seem (and I’ve definitely had days where I felt like curling into a ball, when getting up the next morning takes Herculean energy), this truth about people gets me through.

I think that part of serving in public office is risking public embarrassment or public scorn or ridicule; you definitely take a huge risk. But at the same time, only by putting yourself out there can you really be a part of a movement for change or making a difference. One of my favorite quotes is paraphrased from Teddy Roosevelt, who says, “It’s not the critic who counts. It’s not the man who points out how the strong man stumbled or how the doer of deeds could’ve done better. It’s the man who’s actually in the arena whose face is marred by blood, sweat, and dust, the doer of great deeds.” It says at the end of the quote that if, at the very worst, you fail, at least your place is not with those cold and timid folks who never try at all.

Sometimes the dark moment you’re in is, in the end, actually a gift; that’s also what this epiphany is about for me. That really horrible, most embarrassing moment, at twelve, ended up being a great gift. Not only did it lead me to conquer my fear of public speaking and begin to guide me to this career in speaking and politics, but it helped me see that I love to connect with people in this way. Now when I speak, I feel like I’m not even there anymore, that I’m channeling something larger than myself. And I don’t only feel it when I’m giving a speech, but when I’m having a great conversation with somebody or when I’m watching someone sing or perform; it’s just something about the ability to connect with something universal in everybody. I went from this ignominious beginning when I was very fearful and terrified to stand in front of my peers and give a speech to now, when I speak, I savor the opportunity to try to share my spirit. I can give speeches to large groups, small groups, about facts or technical stuff, or I could even be teaching kids, but the most important thing, to me, is just communicating your spirit. To communicate and share some of your spirit is a very powerful thing.