“The goal is to move from just knowledge, which is information, to understanding, which is awareness.”

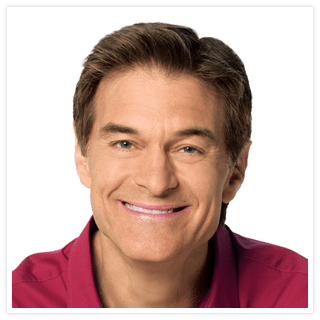

Mehmet Oz, M.D. (Dr. Oz) is a professor and the vice chairman of surgery at Columbia University, the director of the Cardiovascular Institute, the founder and director for the Complementary Medicine Program at New York-Presbyterian Hospital, and the health expert on The Oprah Winfrey Show. He is the Emmy Award-winning host of the daily syndicated television show The Dr. Oz Show and contributes regularly to Time, O magazine, and Esquire. He is the author of more than four hundred original publications, book chapters, and medical books, including the award-winning Healing from the Heart and the bestselling book series YOU: The Owner’s Manual and its follow-ups. Dr. Oz is also one of the founding members of the nonprofit organization HealthCorps, which was created in 2003 in response to his concern about the increasing need to perform heart surgery on thirty-year-olds with arteries clogged from poor diets and sedentary lifestyles-lifestyles that seemed to be reinforced in American schools. (www.healthcorps.org; www.doctoroz.com)

The Interview

I am one of the producers for Dr. Oz’s YOU fitness videos. While I was in New York a couple of months after our first shoot together, we spoke about his epiphany while he was at the hospital. Later, it was a bit surreal for me to listen to the recording of our conversation, especially when he said, “Oh, I’m sorry, they need me now in the OR,” and he rushed off the phone. Right after talking to me about his epiphany, he went into a room and likely saved a life, and for him, that—along with taping his own talk show—is just a normal day.

***

Dr. Oz’s Epiphany as told to Elise Ballard for the book Epiphany: True Stories of Sudden Insights

The goal is to move from just knowledge, which is information, to understanding, which is awareness. ~Dr. Oz

I was chief resident of general surgery at New York–Presbyterian Hospital in New York City, still finishing my training. When you are chief resident, you run the care for people who are in emergency situations. A woman came into the ER with a bleeding ulcer and had almost completely bled out, which means she’d almost lost all the blood in her body. She was a Jehovah’s Witness and her entire family of about thirty people had come in with her. I told the family that I needed to take her into surgery to save her, and if it was successful, I would need to get their permission to give her blood after the surgery. I understood that the Jehovah’s Witness religion has the tenet that a person of their faith cannot receive blood, but I went into surgery thinking that once I got out of the OR they would give permission since the woman would die if we didn’t give her the needed blood.

I completed the surgery successfully and went to the family, excited that we had saved this woman’s life. I believe the spokesperson for the family was her eldest son, and he proceeded to tell me, “We have decided not to give her blood.” I was astounded. I thought maybe they didn’t fully understand the situation, so I asked him if he understood that she would die without receiving the blood. He replied, “We understand. She can’t have the blood.”

You know, I was so angry I couldn’t see straight. I felt insulted. And more than that, I felt I had failed as a doctor to convince them of the gravity of the situation. A “disobeying family”—that’s how I saw them. They were disobeying me. That’s exactly how I felt. How patronizing—but that’s how I thought about it. Here I had busted my butt all that time to save this woman, and now they were going to “strip her from me” just as I was going to “grasp her from the jaws of defeat.”

But then I began to realize that it wasn’t me they were distrusting. It wasn’t that they didn’t believe that what I was saying was true, and that I was trying to bluff them into giving their mother blood that she didn’t want. They actually did believe she would die. They actually took me at face value. They were quite certain that they were signing her death sentence. But they, in their belief system, felt that it was more important for her not to receive the blood and therefore have a better life in the future (somewhere else) than for her to take the blood now to live a little more on this earth.

The epiphany was when I realized that it was out of their love for this woman that they made this decision—because, believe me,the easy decision for them would have been to give her the blood, right? That’s the easy decision, no one could argue with that. They made the hard decision because of their beliefs—because of their loved one’s beliefs. This was a huge epiphany for me because it showed me that it wasn’t all about me and my arguments and how much effort I had made and my thoughts and my conviction about what is right. There were reasons this family had that were very rational according to their belief system. These aren’t reasons I agree with, but they were very rational in their own minds, and it was their judgment to make.

I began to realize that patients don’t always read the same medical textbooks that we doctors read. Too often doctors focus on things that we think are important, not things the patient thinks are important. No longer do I try to talk to patients like they’re me. I try to talk to patients like they’re them.

The way I talk to people—not just patients, but to all people in general—also began to change. I began to think about the worldview from their perspective rather than my own. When you start doing that, you begin to have very different insights. Once you immerse yourself in someone else’s worldview, you can understand their motivations much more effectively. I can really understand your perspective when I try to understand your worldview, which is what healing is all about. The word doctor means “teacher” in Latin. A good teacher gets into the minds of his students and understands what resonates for them, what clicks. The goal is to move from just knowledge, which is information, to understanding, which is awareness. The other thing I began to realize by beginning to relate to people this way is that people truly are the world experts on their own bodies—we always say that in all of our YOU books. They really are. Patients will always tell you their diagnosis. They actually know what’s wrong with them. They may not be able to verbalize it right, they might need your medical insight to appreciate it, but they will tell you exactly what is going on with them. If they are aware or a bit more conscious of what’s going on in their body, it makes them that much better of a healer for themselves.

This realization helped guide the way we write the books, which makes the focus not on us teaching you what we want you to know, but on us sharing with you what you probably want to know. It’s also led to the Integrative Medicine Center at New York– Presbyterian Hospital, where we use alternative or complementary approaches to help patients because we realized and understood that they wanted it, and it’s valid.